Crow’s Nest: Continuing response to Emerald Ash Borer

By Daniel Barringer, Preserve Manager.

We’re still working on alleviating the short-term effects of the devastating Emerald Ash Borer. We’ve taken an inventory of 223 ash trees (Fraxinus spp.) along our roadways at Crow’s Nest Preserve and so far have removed 157 of these trees that have a target onto which we don’t want them to fall (public roads, power lines, buildings, public gathering spaces). Of these targets roadways are the most common. Sixty-six ash trees remain for us to address over the next few years. We started removing the trees before EAB arrived in our region, knowing that once the insect arrived the trees would decline and die after only a few years.

In our forests we’ve left tens of thousands of ash trees that have died or soon will inevitably die. In death they will provide habitat for insects and other species, and in time be replaced by other species (for a discussion of that transition see this June 8 blog entry).

We’re spraying 12 trees with a systemic herbicide at Crow’s Nest to protect them from EAB. These trees are typically young, vigorous specimens in the landscapes around the historic farmsteads at the preserve. So ash is unlikely to disappear completely as a species, but it may come to occupy only a fraction of its historic habitat, perhaps like American chestnut (Castanea dentata). American chestnut still grows at Crow’s Nest and in our region but only remains as small stump sprouts that after a few years succumb to the fungus that kills the above-ground portion of the tree. That species isn’t technically gone but it functionally absent—that is, it isn’t functioning as part of the ecological community it once dominated. As a species ash may suffer the same fate. The loss of chestnut had a cascading effect on the birds, insects and animals which depended on it; we don’t know yet the impact of loss of ash, but it was a major component of floodplain forests and a reliable part of our landscape.

The ash pictured above, though a beautiful specimen, was already declining before the arrival of Emerald Ash Borer—but the dieback is more pronounced now.

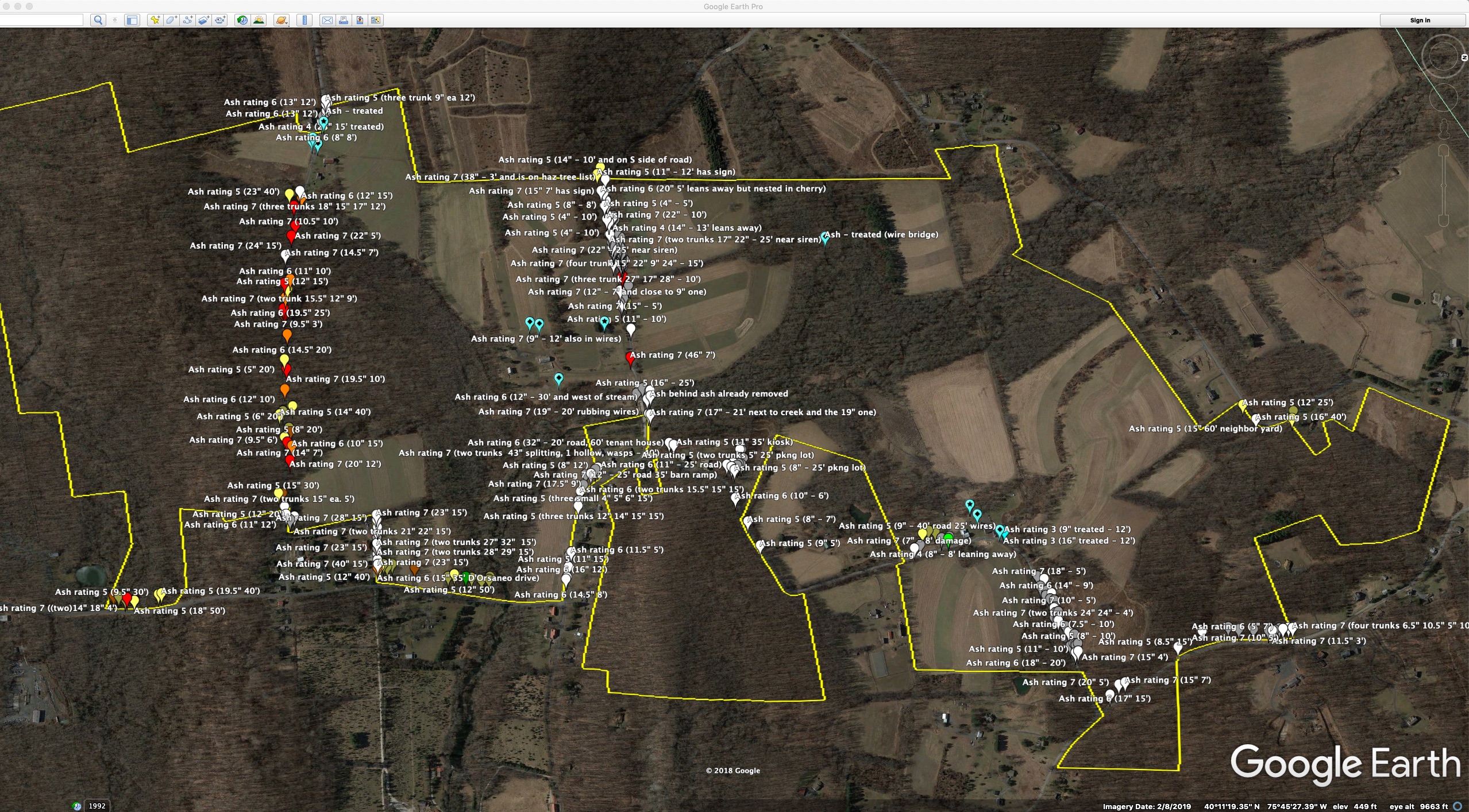

I’ve mapped the progress of our ash tree removals (to make sure we did a thorough enough job in a timely manner). I used Google Earth Pro (TM) to organize the data in the image shown below. I collected approximate location data of each tree in the field with a GPS app on my phone. We have more sophisticated hardware and software for collecting and managing this data, but this method worked well and was cost effective (free).

Each location’s pin is color coded. I prioritized the trees in a scale that progresses from red for the largest and most difficult to orange and yellow for less difficult ones. White pins indicate trees that have been removed (the associated numbers: diameter at breast height—DBH—and distance from target, are ways for us to identify individual trees, even when they are growing very close together). Blue colored pins indicate trees which are being treated with insecticide to protect them from Emerald Ash Borer. As you can see we’ve been working our way from north to south (right to left in this image) and have made a lot of progress.