American Chestnuts. Growing Hope.

December 4, 2020

Illustration of crowds of people gathering chestnuts from 1878

courtesy of the Forest Hill Society

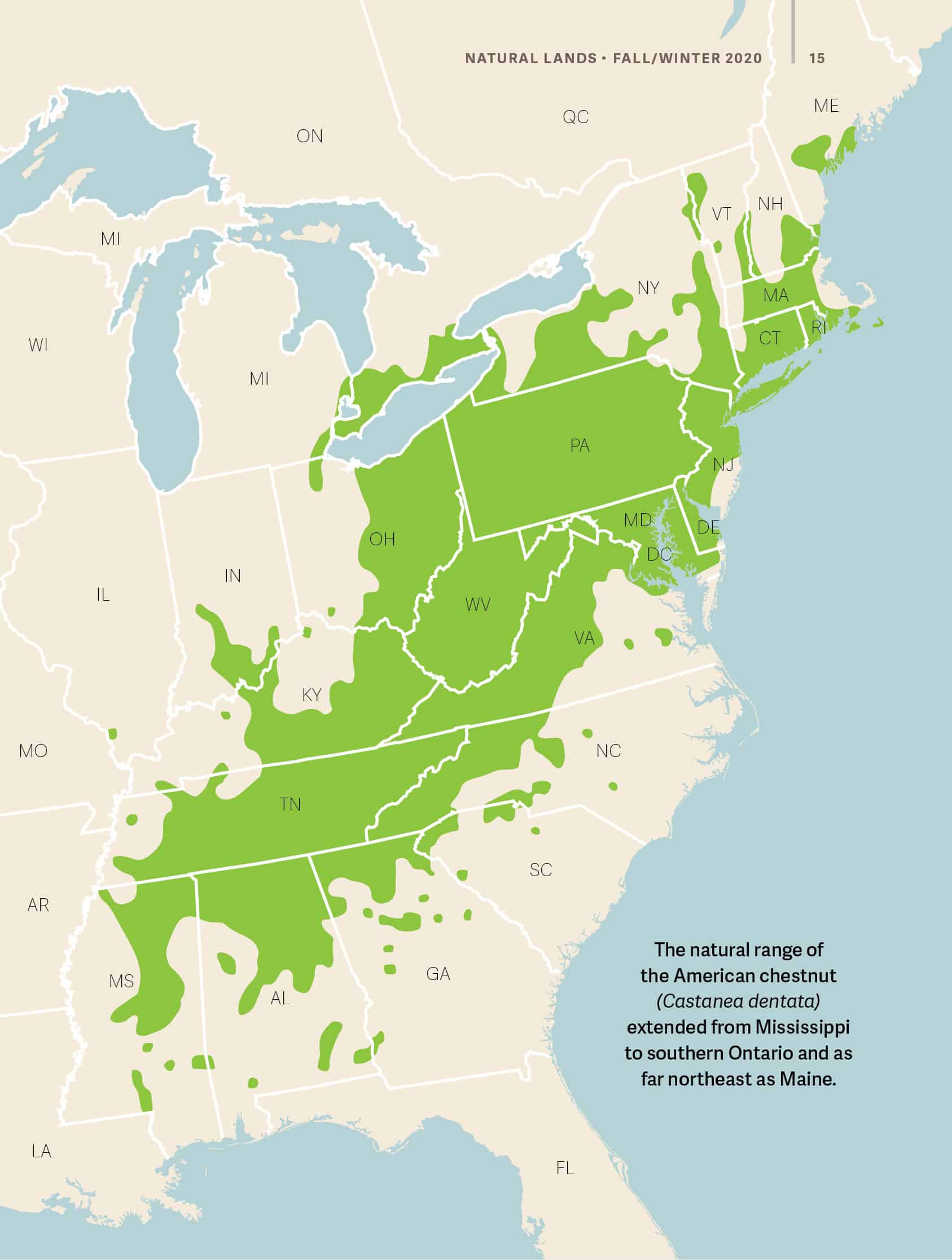

In 1904, the chief gardener for the Bronx Zoo was making his rounds and noticed some of the American chestnut trees had orange speck-les on their bark and withering leaves. Over the next few decades, the parasitic fungus he observed, Cryphonectria parasitica—which had hitchhiked on chestnut trees imported from East Asia—spread like wildfire across the species’ range, from Maine to Georgia. Four billion trees disappeared within 40 years. By 1950, the American chestnut—a species that had evolved 40 million years ago and once dominated eastern North American forests—was effectively extinct.

Or was it?

Chestnut blight kills the above-ground portion of the tree, but the root system can survive to form new shoots that reach about 15 feet tall before being killed by the fungus. Some trees are able to produce nuts before they die, offering hope to scientists and chestnut enthusiasts who are determined to restore the “sequoia of the East.”

In fact, science has brought us tantalizingly close to a blight-resistant version of the American chestnut. But are our Eastern forests—which have changed so much in the 100 years—able to support the species’ return?

It’s hard to overstate the economic, cultural, and ecological importance the American chestnut once had.

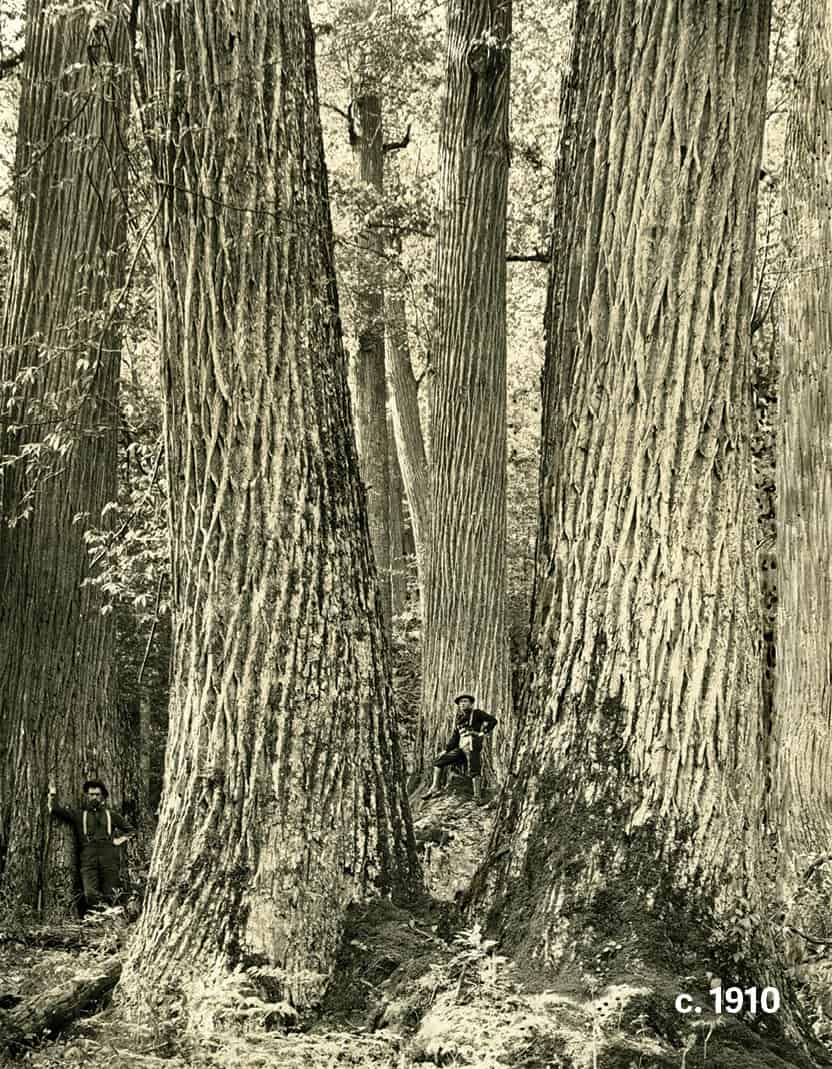

The trees grew fast, straight, and strong, often reaching heights of more than 100 feet. Their wood was rot resistant and straight-grained, making it suitable for framing, furniture, railroad ties, barrels, fencing, flooring, and caskets. Timbermen prized the trees for their ability to be cut and re-sprout. J. Russell Smith, a well-known explorer and geographer once said, “By the time a white oak acorn grows a baseball bat, a chest-nut stump grows a railroad tie.”

The trees grew fast, straight, and strong, often reaching heights of more than 100 feet. Their wood was rot resistant and straight-grained, making it suitable for framing, furniture, railroad ties, barrels, fencing, flooring, and caskets. Timbermen prized the trees for their ability to be cut and re-sprout. J. Russell Smith, a well-known explorer and geographer once said, “By the time a white oak acorn grows a baseball bat, a chest-nut stump grows a railroad tie.”

The profusion of flowers from June-blooming chestnuts was “like a sea with white combers plowing across its surface,” according to naturalist Donald Culross Peattie. Honeybees and other pollinators sought out the blossoms.

Chestnuts produced an abundance of extremely nutritious nuts—as many as 6,000 from a single tree. Native peoples ground them into flour. European settlers roasted them or ate them raw, and also fed them to their livestock. And the nuts were the primary food for wildlife such as bear, deer, elk, squirrel, turkey, and birds including the now-extinct Passenger Pigeon.

The tree’s many attributes justify the decades-long efforts by researchers and amateur enthusiasts to restore the species to eastern forests. In fact, the US Department of Agriculture began a chestnut breeding program as early as 1930, two decades before the species was considered “effectively extinct.” Unfortunately, it was unsuccessful.

The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) was established in in 1983 with the goal of developing a tree that had all the desired traits of an American chestnut but could resist the deadly fungus. Disease resistance was key since the chestnut blight persists in the environment, spread by splashing rain, wind, and insects.

TACF’s program hinges on the science of backcrossing. Plant scientists began by crossing a Chinese chestnut, which is resistant to the fungus, with an American chestnut. The resulting seeds are then planted and tended until the hybrid seedlings flower and can be crossed again. After 30 years and tens-of-thousands of hand-pollinated chestnut trees, researchers have developed a hybrid with enough of the Chinese chestnut’s natural blight resistance to survive but also with a form, growth rate, and wood quality that are indistinguishable from a pure American chestnut.

Ironically, the trees on which the virus hitchhiked to North America may be key to saving the American chestnut.

An alternate realm of research has come from the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, where scientists have focused on genetic modification. Trials have been promising—and controversial. The research has been done in collaboration with TACF, but some of its members resigned after it was revealed that the project had received support from global genetic giants Monsanto and ArborGen.

Yet another approach involves grafting tissue from the very few old survivors—American chestnuts that have somehow resisted the deadly fungus—onto American chestnut rootstock. When these plants flower, nursery staff cross them to one another to develop pure American chestnuts—not hybrids—that have resistance to the virus.

Some believe the species will survive without human intervention. They cite evidence that pollen pulled from lake sediment shows that hemlock trees vanished from North American forests some 5,000 years ago, only to spontaneously reappear a few centuries later. Might the same happen with American chestnuts?

courtesy of the Forest Hill Society

“The rescue and restoration of American chestnut stands as one of the most difficult, prolonged, and complex single-species conservation tasks ever attempted,” said Kim Steiner, professor of forest biology at Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences and director of the University’s arboretum. “However, nine decades after chestnut breeding work began, the reality of a solution is now less a matter of time and conjecture than has ever been the case before.”

But are our modern-day forests able to support a chestnut comeback?

After so many decades of research to develop the perfect tree for reintroduction, experts are now evaluating which conditions will be necessary for that perfect tree to regenerate on a landscape scale.

The USDA Forest Service has launched four studies to evaluate the following:

- site quality: how important is it to chestnut blight resistance?

- deer browsing: what is the impact on chestnut survival?

- prescribed fire: what is the planted chestnut’s response?

- timber harvesting: does three-stage shelterwood harvesting—a more ecologically sensitive alternative to clearcutting—improve chestnut establishment?

The goal of this collaboration between scientists and foresters is to collect enough data to develop a blueprint for the successful, large-scale reintroduction of the American chestnut to the forests of the eastern U.S.

The loss of this sylvan species was, by all accounts, an ecological disaster. While not the first such tragedy caused by humans, the American chestnut blight coincided with the environmental awakening of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Now, when concern for our warming planet is at an all-time high, perhaps the time is right for the American chestnut to make its comeback.

next post

Artists In Phoenixville Transform Utility Boxes Into Works Of Art

December 4, 2020

By Jen Samuel. In Phoenixville, a beautification project to transform ordinary utility boxes on borough streets is underway. The Beautification Advisory Commission of Phoenixville issued […]

continue reading