crafting conservation.

How do conservation easements work?

This centuries-old white oak is one of “Penn’s Trees,” thought to pre-date European colonization.

Jessica Neff-Boyd has been in love with Great Oak Farm for decades, long before she owned the 10-acre property in North Coventry Township, Chester County. She grew up about a mile from the farm, which she and husband Sean Boyd purchased in 2018.

“I remember this area before there was any major development, and I loved roaming the woods and pastures as a kid,” said Jessica. “My family knew the previous owners of Great Oak Farm, and sometimes my dad, my sisters, and I would walk up the road to watch their animals when they were on vacation. To us kids, this farm was a magical place.”

Surely some of that magic is inhabited by the 330-year-old white oak tree that shades the Boyd’s barn along Saint Peters Road. Designated as one of “Penn’s Trees,” it was alive when European settlers arrived and is one of fewer than 100 of these historic trees remaining in the Commonwealth. It is this stately tree that gives Great Oak Farm its name. “After buying the property, we learned about the connections of this land to the Lenape people, how the original deed was held by the Penn family, and all about the oak tree,” said Jessica. “My husband and I knew we had come across something very special, so when we were approached with the idea of a conservation easement we jumped at the opportunity.”

willing landowners.

Jessica and Sean’s love of their land, appreciation for its natural beauty, and enthusiasm for conservation are all critical factors in conserving land. “I always say that conservation begins with a willing landowner,” said Peter Williamson, vice president of conservation services for Natural Lands. “Putting a property under the protection of a conservation easement is usually a lengthy process. It takes patient, motivated landowners for us to be successful in protecting their land.”

A conservation easement is a great tool for individuals, families, and even organizations who want to maintain ownership of their property but also want to ensure that the natural aspects of their land—rolling meadows, quiet forests, and chilly streams—will remain even after they’ve sold the land or passed it on to the next generation. The landowners work with a qualified conservation organization such as Natural Lands to determine a plan that permanently limits a property’s use. The agreement, once finalized, is binding and perpetual; all future owners of the property must abide by it as well. The land trust then monitors the property annually to ensure compliance. That’s how we can say with confidence that land under conservation easement is protected forever.

In 1966, Natural Lands completed the first ever conservation easement in Pennsylvania. Since that time, the organization has protected more than 25,000 acres of land through 427 conservation easements.

assessing value.

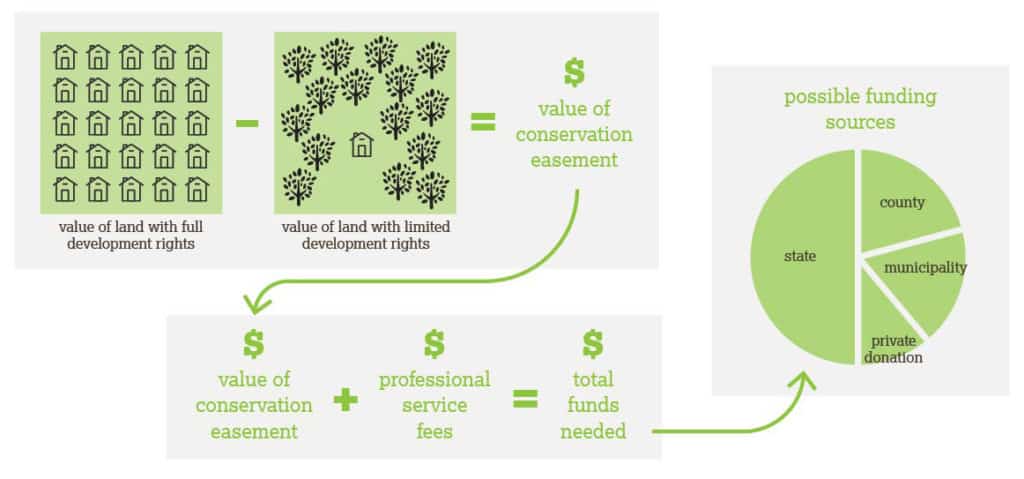

A conservation easement is, in essence, a legal agreement, but it is an agreement that has a monetary value.

The easement’s value—the difference between what the land would be worth with full development rights and what it is worth without those rights—is determined by hiring a qualified appraiser.

A landowner may decide to sell the easement at either full appraised value or at a reduced cost, which may make them eligible for a charitable deduction.

finding funding.

Prior to the early 1990s in Pennsylvania, conservation through easement was accessible only to very wealthy individuals who could afford to donate a conservation easement and pay for the professional fees associated with finalizing the agreement. Adequate private funding simply did not exist for land trusts to be able to offer to pay fair market value for the easement to those who would prefer to sell.

In 1993, however, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania established the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund, which is funded through a small, dedicated portion of the realty transfer tax. In addition, many counties and municipalities also recognized the power of public funding for conservation, establishing their own open space funding programs. Since then, more than $1 billion has been invested in parks, recreation, and open space conservation.

Natural Lands uses these public funds to purchase conservation easements. Every year, the conservation services team must identify, apply for, and be awarded grant monies to cover the costs of each project. Typically, public funders will commit to pay for 50 percent of the total project expense, requiring us to seek other sources, whether public or private, to match the initial commitment.

“Over the years, Natural Lands has gotten really quite skilled at choosing compelling land protection projects and writing persuasive grant applications,” said Peter Williamson, who has spent the past three decades working to save open space for Natural Lands. “Unless it involves an outright contribution, every project lives or dies by whether or not we can find enough grant money to cover some or all the costs. And, when we’re talking about land in sought-after areas, this means sourcing hundreds-of-thousands of dollars.”

The funds are used to cover not only the value of the conservation easement, but also other costs including: the appraisal, the title report and insurance, legal fees to have an attorney prepare the easement document, a survey of the property, a Phase I Environmental Hazard Assessment, Natural Lands staff costs and expenses, and an endowment to support future costs of monitoring and enforcing the easement in perpetuity. These costs generally run between $30,000 and $50,000, de-pending on the size of the property and the complexity of the project.

a forever document.

As each conservation easement is a legal contract, there’s quite a bit of paperwork involved in crafting one. What’s more, Natural Lands follows strict accreditation standards established by the Land Trust Alliance, an organization working to advance conservation at the national level.

“Yes, it’s a lot of work,” says Peter Williamson. “We cross every “t” and dot every “i” to assure that every easement we create will withstand the test of time.”

After Natural Lands’ Board of Trustees formally accepts the easement, the project manager creates a baseline document that describes the property’s features and outlines the conservation objectives. This establishes current conditions and is used in annual monitoring of the easement. The baseline report includes a detailed plant inventory; wildlife observed; maps documenting topography, landscape features, and soil conditions; both aerial and on-site photography; and a list of buildings and other improvements. The information in the baseline also helps support the landowner’s basis for a charitable contribution for the easement (if one is being taken), and provides justification for any public open space funding that has been awarded for the easement.

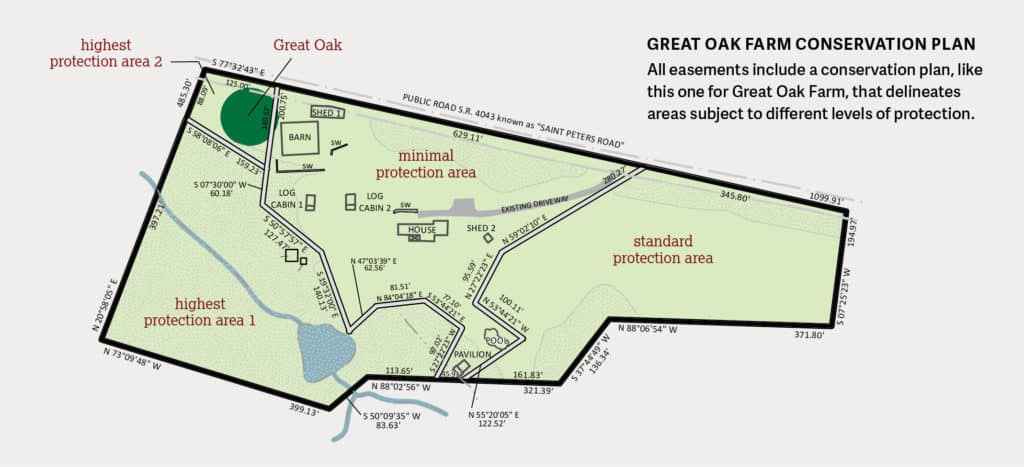

The easement document contains a conservation plan, decided on in consultation with the landowner, that determines any subdivision allowances and delineates areas subject to different levels of protection. The Highest Protection Area (HPA) preserves the most ecologically significant portions of the property, such as wetlands, mature forest, and headwater streams. The Standard Protection Area (SPA) permits uses like farming and timbering. The Minimal Protection Area (MPA) is generally drawn around buildings or other structures.

Once all the documentation is prepared, approved by all parties, and signed at settlement, the conservation easement is recorded at the county Recorder of Deeds where it is public record. This is when we officially celebrate!

forever. one year at a time.

So what happens next? How do all parties ensure that the agreement is honored year after year? This is where land trust monitors begin their important work. Natural Lands staff members spend about 700 hours every year monitoring the conservation easements we hold, plus many more on general easement administration. Easement monitors visit the property, walk the entirety of the land, and note any changing conditions. If the landowner wishes, they can accompany the monitor on the site visit.

monitoring an easement

“Usually site visits are pretty uneventful,” said Megan Boatright, graphic information systems program director and former easement monitor. “But I’ll never forget the time I was out at a property in Montgomery County. The landowner showed us a spot to cross a big stream that bisected his farm. He and I made it across, but a colleague lost his footing and fell into the water. He managed to keep the expensive Trimble device we use for mapping and data collection held up high out of the water, though!”

Fortunately, violations of easements are not common-place. Said Erin McCormick, director of Natural Lands’ conservation easement program, “Occasionally we note the removal of trees in a Highest Protection Area, or a dump site where the homeowner—or sometimes a neighbor—is putting yard debris. There have been a couple notable occasions where the owner installed a driveway that encroached into protected areas or built a shed where it wasn’t permitted.”

When a monitor notes a violation, the landowner is notified in writing and given details on how to correct the issue. Trees have to be replanted, sheds moved, and driveways rerouted. “When we agree to hold an easement, we commit to a significant responsibility—and one that has no expiration date,” noted Williamson.

worth the effort.

Back at Great Oak Farm, the Boyd family couldn’t be more thrilled with their conservation decision.

Said Sean Boyd, “I hope that conserving our property with Natural Lands will further both historical and open space local preservation efforts. Perhaps the biggest benefit of all will be spreading the importance of con-serving these natural areas so that our children and their children will be able to enjoy them.”

“We work with dozens of landowners every year to protect their land,” said Oliver Bass. “Each project is a celebration; we don’t take a single one for granted. All the preparation, all the paperwork, all the months it takes for a conservation easement to finally come together… it’s all part of making sure these lands have a tomorrow. Forever.”

essential philanthropy.

A successful conservation outcome relies on many factors: landowners willing to sell or ease their property, a supportive community, a qualified buyer, and—last but certainly not least—money to make it all happen.

Pyle Farm, Warwick Township, Chester County

“Unfortunately, 50 percent from the state and 50 percent from the county doesn’t equal 100 percent of a project’s cost,” said Jack Stefferud. “It can take years for a land transaction to go from early conversations to the final paperwork. The grants we get from the state, county, and municipalities don’t always cover staff time or unforeseen expenses.”

What is needed is a source of committed, flexible funding that can serve as either the first dollars pledged to a project or as the last mile of funding used to fill the gaps in what is available through public grants. Enter Virginia Cretella Mars Foundation, a charitable organization that, since 2006, has played exactly that role in our land protection successes.

“Simply put, we could not do our work without the Foundation,” said Jack. “Unlike most land protection funders, they extend to us the flexibility we need to fill gaps, close deals, and cover staff time. Over the last 14 years we have leveraged the Foundation’s generous, multi-year grants to protect 40 properties totaling 3,871 acres with a combined value of more than $55 million. In my books, that’s a ‘wow.’”

Fisher Property, Robeson Township, Berks County

Peter Williamson relies on funding from the Foundation to invest time working through transactions in Delaware County, which hasn’t had the dedicated funding of other counties in our region until very recently.

“There isn’t a whole lot of open space left in Delaware County,” Peter offers. “We don’t often get a phone call from someone saying, ‘I have 100 acres I want to give you to conserve.’ Instead it can take months—but more usually years—to seek out relationships, broker conversations, and build prospective deals on those very valuable remaining open parcels. Time spent doing this has a real cost that we need to cover to make our budget each year.”

Victoria Mars, daughter of Virginia Cretella Mars, describes the Foundation’s commitment to conservation, saying, “My mother has always had a passion for open spaces and protecting land from development in her community. If you don’t own land that you can protect directly, the next best thing is to support the work of a quality organization such as Natural Lands, which can. Being able to explore their preserves during these times has been beneficial to my family and increased our belief in the valuable work that Natural Lands does.”

Friends Hospital, Philadelphia

“It costs an average of $40,000 for us to create a conservation easement, and the value of the land is diminished once its development rights are extinguished,” said Peter. “Only the very wealthy can afford to absorb this loss. Public funding has been a game changer in the conservation world, and, when coupled with invaluable support from a private donor like Virginia Cretella Mars Foundation, makes middle class conservation possible.”