Stoneleigh’s Stately Trees.

December 9, 2021

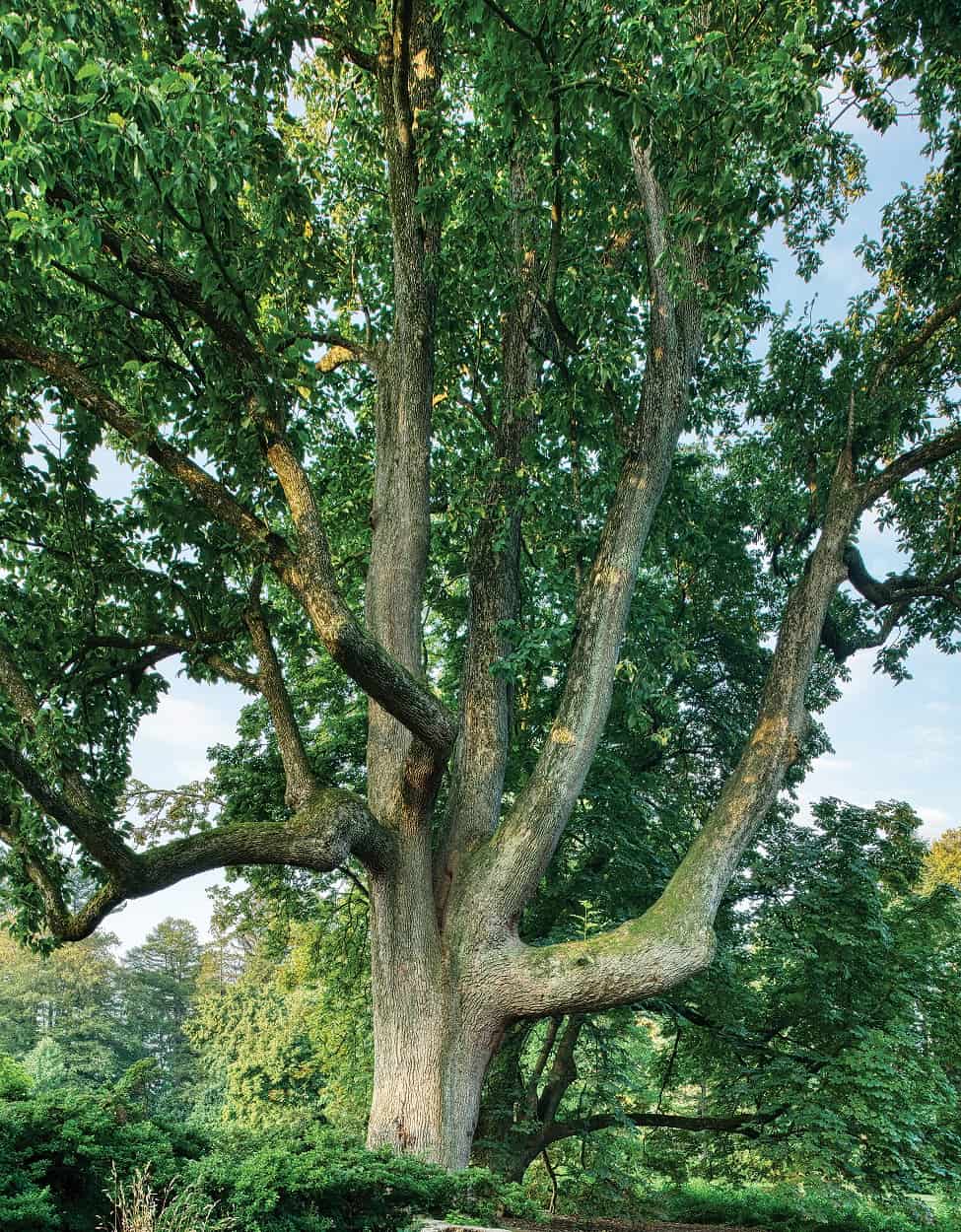

Tall cucumber magnolia tree with broad branches and green leaves

Stoneleigh, Natural Lands’ 42-acre public garden in Villanova, Pennsylvania, is home to magnificent trees representing more than 150 years of landscape design and careful stewardship. Their leafy boughs nurture and comfort us, help clean our air, and provide the garden’s architectural and ecological framework.

Many of Stoneleigh’s largest trees were planted more than a century ago by some of the most influential landscape architects of their day, including the Olmsted Brothers firm. All of these beauties can photosynthesize, stabilize soil, capture carbon, and clean our water, but those native to eastern forests and grasslands best support the life around us. These native trees provide essential food and shelter for insects, which support vertebrates like birds and small mammals, building biodiversity in our communities (and beyond). Several native specimens at Stoneleigh are among the largest of their kind in the state.

Today, Stoneleigh is home to more than 450 different varieties of trees and is a showcase for native plants and sustainable landscape management. To follow are just a few examples of extraordinary trees to see at Stoneleigh.

Photo by David Korbonitz

cucumber magnolia (Magnolia acuminata)

This tree is a native to the eastern US. This species makes a great shade tree and is a fast grower, however the flowers are not showy. Unripe fruits resemble small cucumbers, but ripen to a dark red color.

Native peoples used cucumbertree bark for toothache pain and as a remedy for diarrhea. Settlers combined extracts from the green fruit with whisky for a fever medicine.

eastern arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis)

In 1536, French explorer Jacques Cartier was sailing up the St. Lawrence River looking for the famed Northwest Passage when scurvy sickened his crew. Indigenous Hurons saved them by teaching them to make a curative tea from boiled cuttings from the tree. Fittingly, the species’ name translates to “tree of life” in Latin. The genus name, Thuja, is from a Greek word for perfume. Squeezing the evergreen leaves releases an aroma that is nothing less than nature’s perfume.

Photo by David Korbonits

Though often thought of as a native species to Pennsylvania, eastern arborvitae is actually indigenous to eastern and central Canada south to Northern Illinois, Ohio, and New York.

• number of insects supported: 41

• 6th largest specimen in Pennsylvania

river birch (Betula nigra)

River birches have a special type of flower structure called a “catkin,” derived from the old Dutch word for kitten, because the cylindrical flower clusters resemble a kitten’s tail.

The native river birch is a host plant for Mourning Cloak and Dreamy Duskywing butterflies. In nature this tree is often found in moist soils but is widely adaptable. It can be easily identified by its cinnamon-colored, exfoliated bark and is a great choice for home gardens

• 381 species of butterflies and moths use the Betula as a host plant.

• 10th largest specimen in Pennsylvania

Photo by David Korbonits

eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

This graceful evergreen is the state tree of Pennsylvania. A long-lived tree, the oldest recorded specimen was more than 550 years old.

Hemlocks are susceptible to woolly adelgid, a tiny, sap-sucking insect accidentally introduced from Asia in the 1920s. This pest has killed most of the old-growth hemlocks in the Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah National Park, and has greatly affected eastern forests as well. Because there are more than 140 hemlocks at Stoneleigh it is an excellent place to experience the character of a species once dominant in Appalachia.

southern catalpa (Catalpa bignonioides)

Southern catalpa is native to the Gulf Coast states but is now widely naturalized to much of the United States. Indigenous people called them “catawba,” meaning “winged head,” likely in reference to the winged seeds that emerge from the trees’ long bean-like pods.

The species produces a bitter-tasting chemical compound that deters herbivores. Catalpa sphinx moth caterpillars, however, not only tolerate these compounds, but thrive on them. In fact, the catalpa tree is the sole source of food for this species’ larvae. The caterpillars may defoliate a tree three times in one summer without killing it.

The Stoneleigh catalpa is the third largest of its kind in Pennsylvania, with a massive trunk measuring 204 inches around and a spread of 63 feet. The tree measures 82 feet tall, a remarkable height for a species that usually caps out at half that. Its height is even more remarkable, considering the Stoneleigh tree lost a huge section of its main trunk in a storm decades ago.

• 3rd largest specimen in Pennsylvania

European turkey oak (Quercus cerris)

Native to southern Europe and western Asia, turkey oak is a large, deciduous tree in the white oak group. The acorns, which have a shaggy cap that covers half the nut, give this tree its alternate common name: moss-cupped oak.

This particular tree is of special significance to the Haas family. It was transplanted by John and Chara Haas from their home in Haverford where they lived prior to moving into Stoneleigh in 1964.

• 2nd largest specimen in Pennsylvania

Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha)

Stoneleigh: a natural garden is home to the fifth largest Franklin tree in Pennsylvania. In the summer, large, white flowers burst forth with a scent similar to orange blossom or honeysuckle. The story of Franklinia—somewhat of a horticultural mystery—is as intriguing as the tree is lovely.

Photo by David Korbonits

Thick forests covered our land for millennia before European colonists began to document plant species. Two of these colonists, Philadelphia botanist John Bartram and his son William, encountered a “rare and elegant flowering shrub” in October of 1765 after losing their way during a botanical exploration of southeast Georgia. John served as Royal Botanist for King George III, a role that including traveling throughout the colonies to gather both seeds and living plant specimens.

William Bartram recounted the discovery years later. “We never saw it grow in any other place, nor have I ever since seen it growing wild, in all my travels, from Pennsylvania to Point Coupe, on the banks of the Mississippi, which must be allowed a very singular and unaccountable circumstance; at this place there are two or three acres of ground where it grows plentifully.”

They took seeds and cuttings from these unusual trees and grew them back in their garden outside of Philadelphia, naming the species in honor of their friend Benjamin Franklin. Today, every single living Franklin tree—an estimated 2,000 of them—can be traced back to those grown at Bartram’s garden. That’s because the species has been extinct in the wild since 1803.

Scientists aren’t sure why the plant disappeared. Could it have been fire, flood, or over-collection? One theory involves a soil fungus introduced with the cultivation of cotton.

Another mystery surrounding this plant is whether or not it is actually native to the United States. As Franklin tree was only ever documented in that one location in southern Georgia, some people postulate it was an accidental introduction—as so many non-native species are—brought by the French in the 1600s or on a trading ship.

Franklinia has a reputation for being finicky. It needs rich, acidic, well-drained soil in full sun or light shade. It is not pollution tolerant and is sensitive to root disturbance. But given the right conditions, it’s a spectacular addition to your garden. Or simply visit the magnificent specimen at Stoneleigh, where the mystery lives on.

• 5th largest specimen in Pennsylvania

next post

Natural Lands Preserves Nearly 400 Acres of Lancaster Boy Scout Camp

October 4, 2021

Natural Lands announced today the permanent preservation of 392 acres of vulnerable open space in Elizabeth Township, Lancaster County.