Sentinel Salamanders.

July 8, 2024

red salamander (Pseudotriton ruber ruber)

On a rainy evening in March, Kim White donned boots and a reflective vest in preparation for a long night outdoors. Brandishing a plastic five-gallon bucket and a flashlight, Kim joined a group of other wildlife enthusiasts for the annual “Sally Rally.” This early spring-time effort—organized by French Creek State Park—to help salamanders and other amphibians safely cross our region’s roadways is critical to their survival. So, too, is protection of the wetlands and vernal pools they migrate to for mating season.

Kim and her family live in North Coventry Township, Chester County, not far from Natural Lands’ Crow’s Nest Preserve. Their 7.5-acre property is at the headwaters of Pigeon Creek. Spring’s rainy weather means a portion of the Whites’ land turns into a large pond—the ideal place for salamanders and other amphibians to mate. The pond is ephemeral—it disappears in warmer, dryer weather—which means there are no fish to eat the salamander eggs or larvae.

slimy salamander (Plethodon glutinosus), photo by Dan Barringer

Eastern hellbenders and common mudpuppies are two of the more colorfully named salamander species that call Pennsylvania home. In fact, you can find 22 species of salamander in the Commonwealth. They’re a shy bunch—secretive and nocturnal—and quite particular about their neighborhood. Because their smooth skin must remain moist, they can live only in damp areas, and they need vernal—or seasonal—pools to reproduce. Several of these species are at risk, including the rare Jefferson salamander, a species of “special concern,” and the blue spotted salamander, an endangered species. Other at-risk amphibians in our region include Fowler’s toad and Cope’s gray treefrog.

biodiversity in the Big Woods.

Amphibians are considered environmental bellwethers. Since they live both on land and in water and their bodies are permeable, they are sensitive to changes in both environments and can warn us when things are out of balance. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) describes salamanders in particular as “sentinels of ecosystem integrity.” Their population trends can be detected more quickly and with fewer years of monitoring effort than other vertebrate species, including birds, small mammals, and other amphibians.

Hopewell Big Woods

Globally, one-third to one-half of all amphibian species are threatened with extinction, with probably more than 120 species already gone in recent years. They are not alone. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, we are currently facing an extinction crisis that is between 1,000 and 10,000 times higher than the natural species extinction rate. The leading threats include habitat destruction, pollution, the spread of invasive species, climate change, population growth, and other human activities.

We know that saving open space is key to combatting these stresses. It’s no coincidence that salamanders thrive—even if they need a little help crossing the road—in and around French Creek State Park and private properties like Kim White’s. These are part of a much larger conservation landscape called Hopewell Big Woods, the largest remaining contiguous forest in southeastern Pennsylvania. Located in northern Chester County and southern Berks County, the region is approximately 73,000 acres or 114 square miles. In addition to the state park, the area includes Hopewell Furnace National Historic site, state game lands, county parks, and our 712-acre Crow’s Nest Preserve. In fact, more than 21,000 acres are conserved to date.

Hopewell Big Woods is one of the region’s most important resources for wildlife, clean water, climate resilience, and outdoor recreation—and it did not become that by accident. The area was identified as a priority for conservation in 1998 by Natural Lands conservation staff when satellite photographs revealed 28,000 acres of unbroken forest around the state park. Dr. Jim Thorne, then Natural Lands’ senior director of science, created a conservation plan for the landscape with support from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

In 2001, Dr. Thorne presented his research and recommendations to a group of 15 public entities, non-profits, and private individuals with an interest in the region, and the Hopewell Big Woods Partnership was born. Now comprised of some 40 government agencies, private non-profits, and municipal entities, the Partnership works to protect and preserve the landscape while enhancing its enjoyment for this and future generations.

new tools for conservation.

It’s no surprise that the technology that allowed us to see Hopewell Big Woods from space in the late 90s has evolved significantly since then. Today, we use what is called geographic information systems (GIS) to create, manage, analyze, and map all types of data. And we are leveraging the power of these systems as we wrestle with this big picture question: where can saving open space best combat the stresses our region faces and help build resilience?

“The reality is that we can’t save every acre of remaining open space in eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey,” said Todd Sampsell, Natural Lands’ vice president of conservation. “So, we must ask ourselves: Which conservation projects are most important and have the most impact?

“We’ve identified some of the major, big-picture concerns impacting our region and begun collecting data relevant to those issues to analyze using mapping software,” said Todd.

We’ve queried individual data sets: Where are the important migration corridors and contiguous forests to support at-risk wildlife species, like the salamanders and toads? Which parts of our region are most susceptible to flooding? Where is development pressure the greatest? Where can we prevent stream impairment to improve water quality? Where are the population centers and heat islands? Where is there inequitable access to the outdoors?

By mapping the answers to each of these questions using existing data, Natural Lands has identified places in the region where stressors and conservation priorities overlap. These overlapping locations are where our conservation work can help landscapes and human communities withstand stressors—big storms, changing weather patterns, floods and drought, loss of habitat—and bounce back quickly after a significant disturbance. That’s resilience.

“I applaud our conservation team’s commitment to data-informed decision making,” said Oliver Bass, president of Natural Lands. “This tool gives us a blueprint for where we can have the greatest impact. The successful outcomes achieved by our colleagues and partners in Hopewell Big Woods are an inspiration and a model of the type of proactive conservation we look to emulate and build upon.”

Unami Hills. food, shelter, safe passage.

A landscape’s capacity to support a diversity of wildlife—through food, shelter, and safe paths for migration—is one example of several factors Natural Lands uses to determine where the organization can help build resilient landscapes. Identifying and pursuing protection of ecologically valuable properties means saving migration corridors and essential habitat for at-risk species.

Unami Hills is an interconnected mosaic of mature woodlands, rocky outcrops, and more than 24 miles of well-protected waterways. The 15,000-acre area is an extraordinary combination of scale, species diversity, streams, and sylvan sanctuaries.

As Todd Sampsell put it, “Unami Hills is clearly a priority from a wildlife standpoint. Once we layered in the additional data sets—climate resilience, important water resources, prevention of sprawl—the landscape really lit up. It’s an area we’ve worked in for years and—from a resiliency and impact standpoint—it’s an important place for our continued land protection efforts.”

The area was originally inhabited by the Unami band of the Lenape. Unami translates to “People Who Live Down-River.” Due to the massive boulders and outcrops, the land was less desirable for farming by Native peoples and for the European colonists who followed.

The mixed deciduous interior forest provides a home for gray fox, mink, eastern coyote, and wood frog. Bird species that rely on deep woodlands thrive here: Scarlet Tanager, Louisiana Waterthrush, American Redstart, and Prothonotary Warbler. At least 30 species of concern have been observed.

The Unami Hills conservation area has roughly 31 miles of perennial streams that support aquatic life like redbelly turtle, northern red salamander, and pineland pimpernel.

To date, nearly 2,500 acres in the Unami Hills are under Natural Lands’ permanent protection.

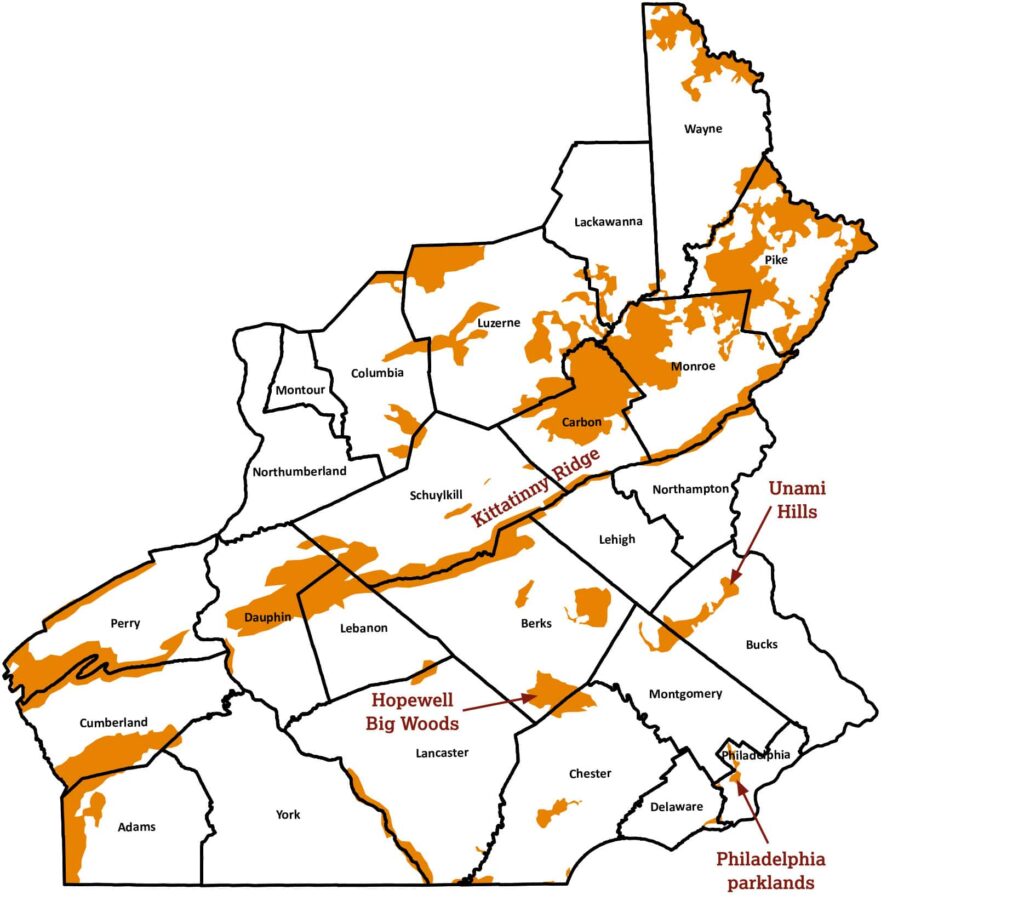

This map, produced by Natural Lands’ GIS Director Megan Boatright, shows the most important remaining wildlife habitats and migration corridors in southeastern Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, the Kittatinny Ridge and forested areas in the Poconos are prominent habitats in our region. However, other more suburban and urban greenways pop out, like Hopewell Big Woods, parklands in urban Philadelphia, and the Unami Creek greenway in northern Montgomery and Bucks Counties.

next post

Looking Downstream.

July 8, 2024

About a half-mile as the crow flies from the Philadelphia Airport, amid the tidal marsh and mudflats at the southernmost point of Darby Creek, a […]

continue reading