Looking Downstream.

July 8, 2024

The overflowing Darby Creek inundated roads in Darby Township, Delaware County, following Tropical Storm Isaias in August 2020.

John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, Shutterstock

About a half-mile as the crow flies from the Philadelphia Airport, amid the tidal marsh and mudflats at the southernmost point of Darby Creek, a conservation movement began. It started with a handful of birdwatchers led by an intrepid accountant—the founder of Natural Lands—who worked to save this watery habitat from ruin. They prevailed, but this was just one chapter in a long and sometimes fraught story of a downstream habitat and the communities that live and work there.

Historically, the area at the bottom of the Darby Creek Watershed stretched for more than 5,000 acres and was a plentiful landscape for fishing, hunting, and foraging. By the time Allston Jenkins and fellow activists stepped up in defense of the habitat in 1953, Tinicum Marsh had shrunk to just 200 acres after a century of infill and urban expansion. Their conservation success prevented a plan to dump dredging spoils from the Schuylkill River into the Marsh. Instead, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers turned to the nearby neighborhood of Eastwick, pumping about three million cubic yards of polluted sediment there.

At that time, Eastwick was one of the only racially integrated sections of Philadelphia with Polish and Italian immigrants living side-by-side with African Americans. Residents enjoyed a semi-rural lifestyle with access to nearby waterways for swimming, bathing, and crabbing. Even with a thriving population of some 19,000 people, Eastwick was still 60 percent open space with the wetlands absorbing periodic overflow from Darby and Cobbs Creeks.

Just a few years later, in 1958, city planners targeted the area as a place to relocate low-income populations being displaced by redevelopment projects in North and West Philadelphia. This “urban renewal” plan demolished 4,000 houses and displaced more than 8,000 people. Development continued in fits and starts through the 1980s.

Over the decades, as the marshland was filled in and paved over, Eastwick has experienced increasingly severe flooding. Most of the land in the neighborhood is between four and 12 feet above sea level. In the past two decades, the Philadelphia Water Department estimates 130 properties have flooded 10 times or more, and the entire area was under four feet of water during Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Since Floyd, parts of Eastwick have been severely damaged by three tropical storms and three hurricanes.

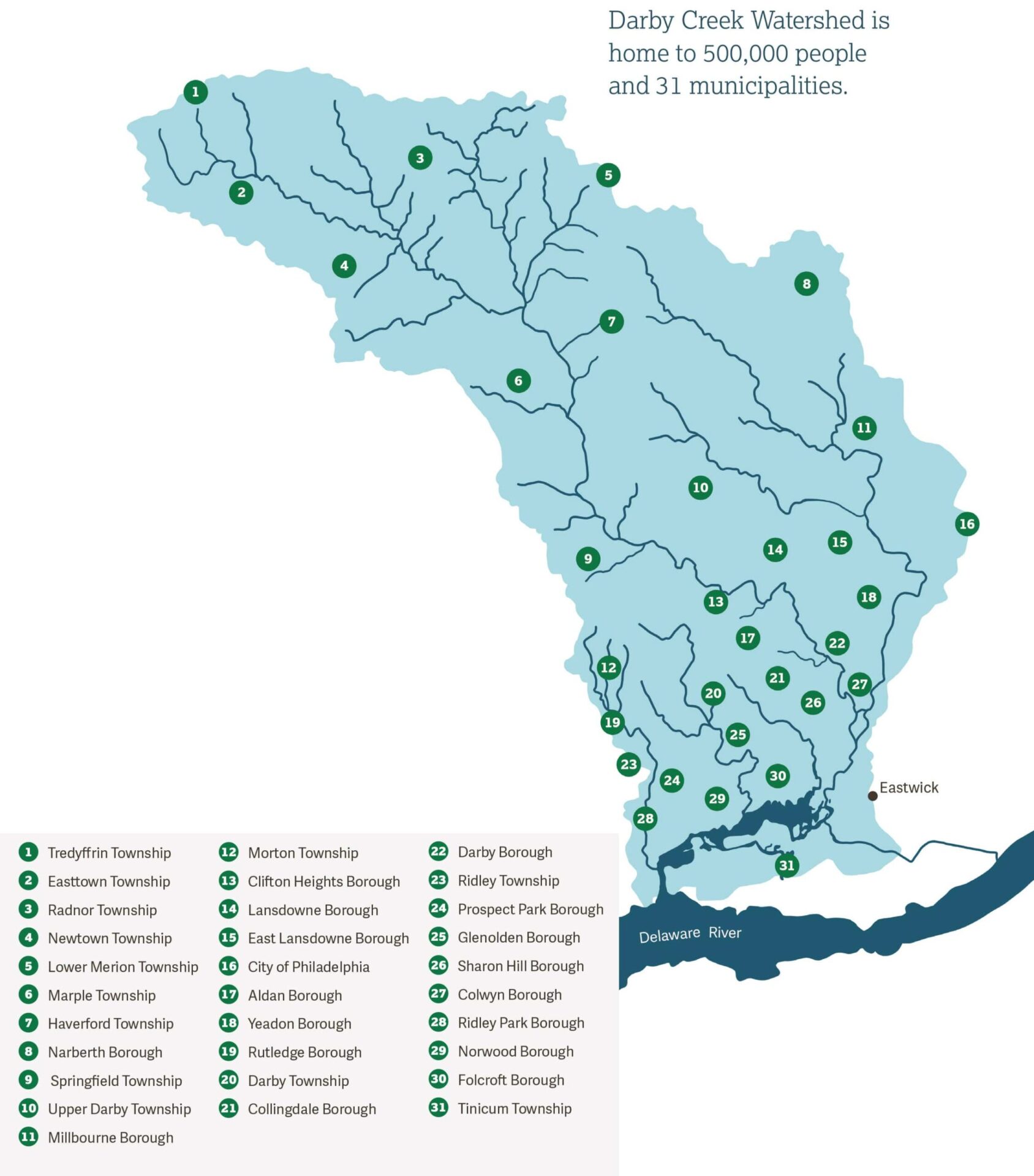

Recently, Darby Creek Valley Association enlisted Natural Lands to develop a Resilience, Conservation, and Management Plan for the Darby Creek Watershed. All the water that falls on this 78-sqaure-mile area makes its way into the streams and creeks—123 linear miles of waterways in total—that feed Darby Creek. About half a million people live in this densely populated geography, which spans four counties and 31 municipalities. Eastwick is at the very southern end of this vast area.

Said Rick Tralies, senior director of planning with Natural Lands, “Everything flows to Eastwick and the Tinicum Marsh. Land use decisions in Radnor, Haverford, and Lower Merion impact the communities downstream, which is why a successful plan must include inter-municipal cooperation.”

Intensified storm events, disruption of weather patterns, and more severe heat waves in recent years have compounded the stresses on the watershed, accelerating the need for a plan that takes these increased stressors into account.

“In addition, a worthy plan for the Darby Creek Watershed must recognize the racial and socio-economic disparities among our watershed communities. Lower-

income communities shoulder disproportionate pollution burdens and relative lack of access to watershed resources,” said Dr. Jaclyn Rhoads, president of Darby Creek Valley Association’s Board of Directors.

The planning effort got underway last year with funding from the Delaware County Green Ways program, the Foundation for Delaware County, Darby Creek Valley Association, and the William Penn Foundation. The planning process includes mapping analysis, key person interviews, a study of precedents in other communities, and a review of zoning, subdivision, and land-development ordinances at each of the 31 townships within the watershed. While the project is only nearing the halfway point, the partners are determined to create an actionable, cohesive, and climate-resilient blueprint for the Darby Creek Watershed.

The planning effort got underway last year with funding from the Delaware County Green Ways program, the Foundation for Delaware County, Darby Creek Valley Association, and the William Penn Foundation. The planning process includes mapping analysis, key person interviews, a study of precedents in other communities, and a review of zoning, subdivision, and land-development ordinances at each of the 31 townships within the watershed. While the project is only nearing the halfway point, the partners are determined to create an actionable, cohesive, and climate-resilient blueprint for the Darby Creek Watershed.

“We cannot undo the past 400 years of stream degradation, but we can begin to better manage the watershed,” said Rick. “A plan won’t stop climate change and flooding, but it can help communities be more prepared for its effects.”

He added, “And of course a plan can’t reverse decades of environmental and racial injustice. We must recognize the importance of listening to community members within the watershed, hear their needs and concerns, and engage with them in shaping strategies.”

next post

Depth Of Field.

July 8, 2024

David Korbonits knows his way around a garden. He spent 28 years as a horticulturist at Mt. Cuba Center in Hockessin, DE, before retiring in […]

continue reading