Into The Woods.

January 3, 2024

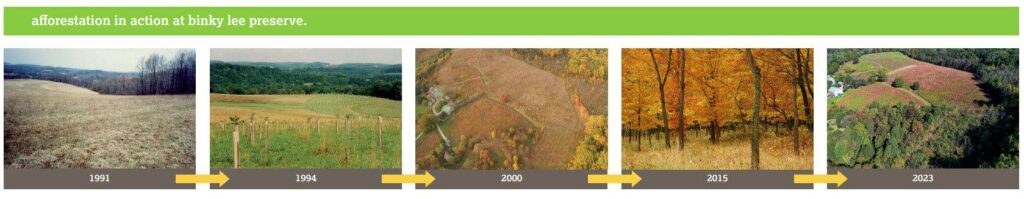

The forest at Binky Lee Preserve

Darin Groff was 19 when he began working for Natural Lands. It was 1990. George H. W. Bush was in the White House, the Internet was in its infancy, and cigarettes had just been banned on domestic flights. Binky Lee Preserve, an 89-acre property in Chester Springs, Chester County, had just been donated to Natural Lands by the Seiple family, who’d named the farm after a beloved horse.

Darin Groff. Photo by Mae Axelrod.

“Most of the land was in hay back then,” Darin recalls. “Harvesting it was a challenge because Binky Lee is so hilly, and we worried we’d flip the tractor. This land isn’t suited for farming—it’s way too steep and the soil just erodes. It’s meant to be a forest.”

Binky Lee, like the rest of southeastern Pennsylvania, had been a forest for millennia before it was colonized by Europeans. When William Penn first visited in 1682, almost 99 percent of the nearly 29 million acres that is now Pennsylvania was covered in trees. Adequate rain, rich soil, and moderate temperatures make our region ideal for forest growth. In fact, if you leave the land to its own devices, farm fields, meadows, and lawns will quickly give way to woody plants.

So, Darin started planting trees. White and red oak, American sycamore, white pine, sugar maple, ash, and black gum, just to name a few. About 50,000 of them over the decades, with help from land stewardship colleagues and volunteers.

Thirty-three years later, Binky Lee Preserve is a thriving example of the transformative effect of afforestation. A third of the now 112-acre property is wooded with the balance as meadow, which Darin—who’s been preserve manager there for decades and also serves as a regional stewardship manager—mows annually to control woody and invasive plant growth.

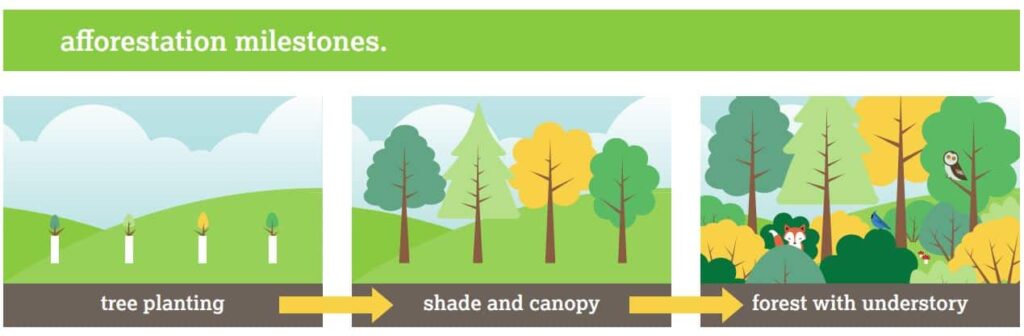

This practice of creating a forest where one hasn’t been for a long time is called afforestation. It’s distinguished from reforestation, which is the replanting of trees in an area where the forest ecosystem is still in place.

Photos by Harry Carl, Mike Coll, Bill Moses, Mark Williams

protect those plants.

Examples of Natural Lands’ afforestation efforts can be seen across our network of 40+ nature preserves in eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey. It is often the rows of green plastic tubes that tip-off preserve visitors to a forest-in-progress.

Tree tubes are essential to seedling survival. They protect the baby trees from deer and create a mini-greenhouse effect that can stimulate early tree growth.

Photo by Alessandra Manzotti

The trees are planted in rows spaced about 10 feet apart, leaving enough room for mowing in between the rows, which keeps invasives at bay. While this even planting pattern may look unnatural at first, other native species—like tuliptree and spicebush—fill in the gaps through natural succession. Once the trees are large enough and begin shading the ground beneath—usually after about a decade—our land stewards can stop mowing around them and address invasives as needed.

The final step in an afforestation project is to help these new forests establish healthy understories. Nature often provides this essential layer on its own as seeds drop from nearby trees or helpful birds, but we accelerate this process whenever we can. Planting hardy native shrubs that can outcompete invasive species helps establish forest understory more quickly, protecting our investment and minimizing the maintenance needed for these new woods to thrive.

worth the work, and the wait.

The oldest of Binky Lee’s new forests are more than 30 years old. Is all that work worth the wait? The wildlife thriving in these woods answer with a resounding YES.

These woods, like the others we are growing around the region, create essential habitat for wildlife, including neotropical birds that rely on dense forests for food, breeding, and shelter. They establish migratory corridors by connecting to already forested areas. They bolster important ecological services like slowing and soaking up floodwaters, producing oxygen, drawing carbon from the atmosphere, and cooling temperatures. When planted along streams, they prevent erosion, reduce flooding, and help improve aquatic life and water quality.

What’s more, creating and improving forest habitat is perhaps the most cost-effective way to tackle the climate crisis. As trees grow, they absorb and store the carbon dioxide emissions that are driving global warming. A 2019 study reported in the journal Science calculated that planting a trillion trees worldwide would suck up nearly 830 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere—equal to the amount of carbon pollution humans have created in the past 25 years.

“What blows my mind is the scale,” said Tom Crowther at the Swiss university ETH Zürich, who led the research. “I thought [forest] restoration would be in the top 10, but it is overwhelmingly more powerful than all of the other climate change solutions proposed.”

And, in its January 2020 report, “CarbonShot,” the World Resources Institute suggested that reforestation and afforestation will be key for the U.S. to have any hope of reaching carbon neutrality by 2050.

adaptive approaches.

Despite the incredible impact trees can and will have on climate in the coming decades, changing weather patterns and rising temperatures require us to adjust which species we include in our afforestation projects.

Northern tree species that are close to the southern extent of their range in Pennsylvania face increased stress and population declines, while southern or temperate species are spreading northward. Natural forest regeneration is threatened as vulnerable seedlings succumb to weather extremes like drought and deluges. Forest pests and pathogens, as well as invasive species, are expanding their range as temperatures warm, taking advantage of stressed trees.

“All of those ash trees we planted in the 1990s and 2000s? They’ve all died because of the emerald ash borer,” says Darin of the destructive beetle that has decimated ash populations across the country.

Sometimes, the changes create impacts we don’t expect. “We now have longer growing seasons—by about seven to 10 days—which gives plants more time to grow,” said Dr. Marc Abrams, Penn State professor of forest ecology and tree physiology. “This has been highly evident in my tree ring research where we routinely see trees putting on much more diameter growth now than in the past. This is particularly evident in young trees, but we see it in old trees as well. This is remarkable. Old trees should be slowing down, not speeding up.”

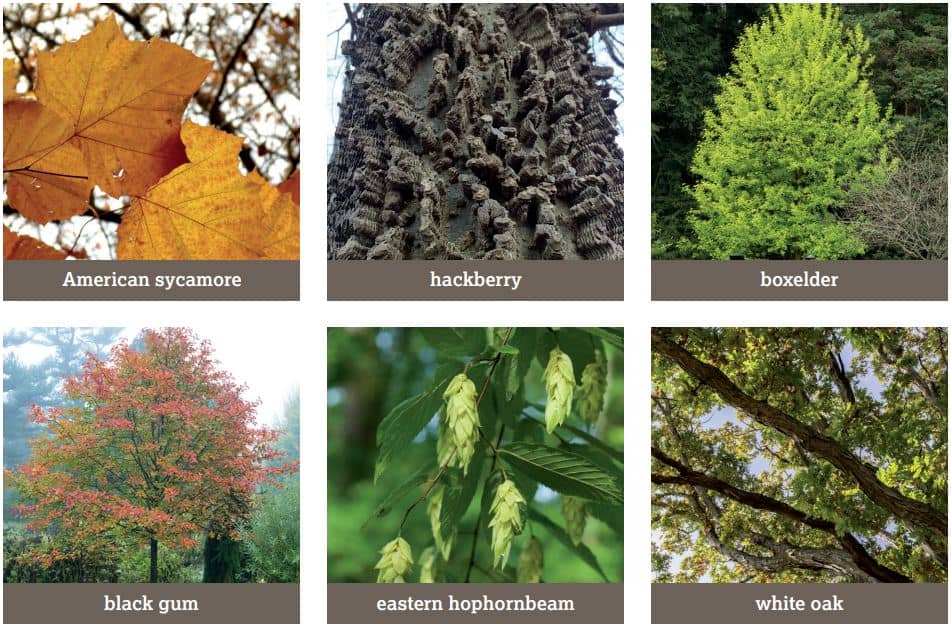

“Natural Lands has begun selecting more climate-resilient species for our afforestation projects. We’re putting in more American sycamore, hackberry, boxelder, black gum, and eastern hophornbeam,” said Gary Gimbert, vice president of preserve stewardship. “Instead of red oak, we’re selecting black oak, white oak, and chestnut oak species.”

Darin adds, “The climate is changing so rapidly—tree species don’t have time to adapt. So, we adapt instead.”

Photos by Creative Commons/Katja Schultz, Emma Schad, David Korbonits, David Korbonits, Creative Commons/Eric Hunt, Mae Axelrod

the giving tree.

Every 70 days, a mature oak tree produces enough oxygen to support a human for one year.

Its deep roots allow rainwater to infiltrate the soil, which reduces flooding during storms and recharges groundwater supplies.

What’s more, oak trees are food for caterpillars, which are essential food for baby birds. More than 500 species of moths and butterflies lay eggs that hatch into caterpillars on native oaks. In contrast, many popular ornamental species like Japanese maples, crepe myrtles, Korean dogwoods, and Callery pears can’t support a single species of native moth or butterfly.

Though an oak tree can grow to 100 feet with a similar crown spread, even homeowners with modest yards can plant one. Because their roots grow so deep, they aren’t likely to buckle pavement. And their open canopy allows sunlight to penetrate to lawns below.

Photo by Laurie Carrozzino Photography

When we plant an oak or any other tree species at our preserves or Stoneleigh: a natural garden, we hope for it to live a long and healthy life. But trees keep giving even as they decline.

A dying tree is host to myriad insects, which woodpeckers and other animals feast on. The soft wood gives way, creating cavities that provide shelter and nesting space for owls, kestrels, raccoons, and opossums. Standing dead trees—also called snags—provide perches for hawks and other raptors. Once the tree falls, lichens and mushrooms break it down and return nutrients to the soil, which is taken up by other trees and plants. As long as the ground isn’t yet frozen, winter is a great time to plant, as trees are dormant and less prone to stress. Plant an oak tree today!

next post

Warwick Woods Restoration Update

December 31, 2023

By Daniel Barringer, Preserve Manager. I’m surprised to realize that I have written very little about the largest land stewardship project we’ve undertaken here in […]

continue reading